KURDISTAN: WHAT IS IT? AND WHO ARE THE KURDS?

Between 20 and 30 million Kurds inhabit a

mountainous region straddling the borders of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran and

Armenia. They make up the fourth-largest ethnic group in the Middle East, but

they have never obtained a permanent nation state.

|

| A map of Kurdistan the land of Kurds |

In recent decades, Kurds have increasingly

influenced regional developments, fighting for autonomy in Turkey and playing

prominent roles in the conflicts in Iraq and Syria, where they have resisted

the advance of the jihadist group, Islamic State (IS).

Where do they come from?

The Kurds historically led nomadic lives

revolving around sheep and goat herding throughout the Mesopotamian plains and

the highlands in what are now south-eastern Turkey, north-eastern Syria,

northern Iraq, north-western Iran and south-western Armenia.

Middle East map showing Kurdish areas

Today, they form a distinctive community,

united through race, culture and language, even though they have no standard

dialect. They also adhere to a number of different religions and creeds,

although the majority are Sunni Muslims.

Kurdistan: A State of Uncertainty

|

| Independent Kurdish state |

Why don't they have a state?

Despite their long history, the Kurds have

never achieved a permanent nation state

In the early 20th Century, many Kurds began

to consider the creation of a homeland - generally referred to as

"Kurdistan". After World War One and the defeat of the Ottoman

Empire, the victorious Western allies made provision for a Kurdish state in the

1920 Treaty of Sevres.

Such hopes were dashed three years later,

however, when the Treaty of Lausanne, which set the boundaries of modern

Turkey, made no provision for a Kurdish state and left Kurds with minority

status in their respective countries. Over the next 80 years, any move by Kurds

to set up an independent state was brutally quashed. Aiming to change the outcome of World War

One.

Why are Kurds at the forefront of the fight

against IS?

Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga fighters have been

fighting Islamic State in northern Iraq

In mid-2013, IS turned its sights on three

Kurdish enclaves that bordered its territory in northern Syria. It launched

repeated attacks that until mid-2014 were repelled by the Popular Protection

Units (YPG) - the armed wing of the Syrian Kurdish Democratic Unity Party

(PYD). The turning point was an offensive in Iraq in June that saw IS overrun

the northern city of Mosul, routing Iraqi army divisions and seizing weaponry

later moved to Syria.

|

| Kurdish Peshmarga fighting against ISIS on the front line |

The jihadists' advance in Iraq also drew

that country's Kurds into the conflict. The government of Iraq's

semi-autonomous Kurdistan Region sent its Peshmerga forces to areas abandoned

by the army.

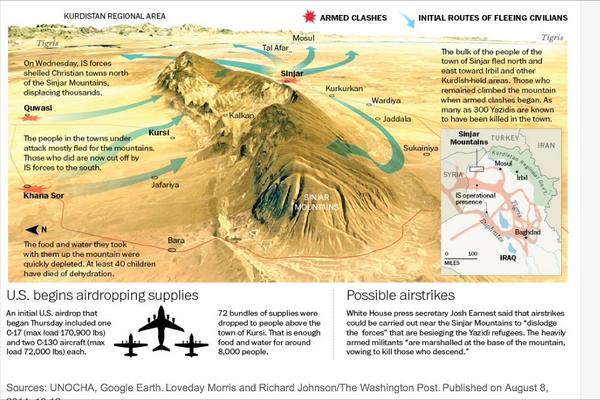

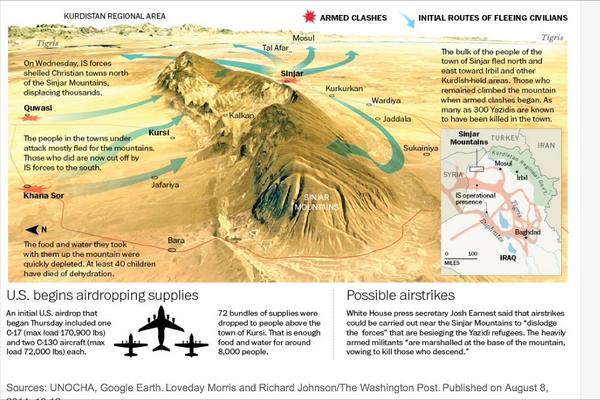

For a time there were only minor clashes

between IS and the Peshmerga, but in August the jihadists launched a shock

offensive. The Peshmerga withdrew in disarray, allowing several towns inhabited

by religious minorities to fall, notably Sinjar, where thousands of Yazidis

where sheltering.

|

| Sinjar Mountain in Kurdistan |

Turkish military personnel deployed along

the Syrian border have not intervened in the battle for Kobane. Alarmed by the Peshmerga's defeat and the

potential massacre of the Yazidis fleeing Sinjar, the US launched air strikes

in northern Iraq and sent military advisers. European countries meanwhile began

sending weapons to the Peshmerga. The YPG and Turkish Kurdistan Workers' Party

(PKK) also came to their aid.

Although the jihadists were gradually

forced back by the Peshmerga in Iraq, they did not stop trying to capture the

Kurdish enclaves in Syria. In mid-September, IS launched an assault on the

enclave around the northern town of Kobane, forcing more than 160,000 people to

flee into Turkey.

Despite this, Turkey refused to attack IS

positions near the border or allow Kurds to cross to defend it, triggering

Kurdish protests and a threat from the PKK to pull out of its peace talks with

the government. However, it was not until mid-October that Ankara agreed to

allow Peshmerga fighters to join the battle for Kobane. Syria's Kobane no longer so isolated.

Why is Turkey reluctant to help the Kurds

in Kobane?

|

| Abdullah Ocalan face on flags held by Kurds |

PKK supporters demonstrate in Paris after

the arrest of Abdullah Ocalan (17 February 1999)

Jailed PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan began

peace talks with the Turkish government in 2012. There is deep-seated hostility between the

Turkish state and the country's Kurds, who constitute 15% to 20% of the

population.

Kurds received harsh treatment at the hands

of the Turkish authorities for generations. In response to uprisings in the

1920s and 1930s, many Kurds were resettled, Kurdish names and costumes were

banned, the use of the Kurdish language was restricted and even the existence

of a Kurdish ethnic identity was denied, with people designated "Mountain

Turks".

|

PKK fighters who are well known for having a high population

of female fighters |

PKK fighters in parade in northern Iraq (11

August 2005)

More than 40,000 people have been killed

since the PKK launched an armed struggle in 1984

In 1978, Abdullah Ocalan established the

PKK, which called for an independent state within Turkey. Six years later, the

group began an armed struggle. Since then, more than 40,000 people have been

killed and hundreds of thousands displaced.

In the 1990s the PKK rolled back on its

demand for independence, calling instead for greater cultural and political

autonomy, but continued to fight. In 2012, the government and PKK began peace

talks and the following year a ceasefire was agreed. PKK fighters were told to

withdraw to northern Iraq, but clashes have continued.

Turkish soldiers filter refugees crossing

the border near the Syrian town of Kobane (28 September 2014). Turkey has allowed in more than 160,000

people, most of the Kurds, fleeing the fighting around Kobane. Although Ankara considers IS a threat, it

also fears that Turkish Kurds will cross into Syria to join the PYD - an

offshoot of the PKK - and then use its territory to launch attacks on Turkey.

It has also said it is not prepared to step up efforts to help the US-led

coalition against IS unless the removal of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad is

also one of its goals.

What do Syria's Kurds want?

Salih Muslim, head of the Democratic Unity

Party (PYD) receives condolences from Syrian Kurds after his son Servan was

killed in fighting with jihadist militants (15 October 2013)

The Democratic Unity Party (PYD) is the

dominant force in Syria's Kurdish regions

Kurds make up between 7% and 10% of Syria's

population, with most living in the cities of Damascus and Aleppo, and in

three, non-contiguous areas around Kobane, the north-western town of Afrin, and

the north-eastern city of Qamishli.

|

| YPG fighters |

Syria's Kurds have long been suppressed and

denied basic rights. Some 300,000 have been denied citizenship since the 1960s,

and Kurdish land has been confiscated and redistributed to Arabs in an attempt

to "Arabize" Kurdish regions. The state has also sought to limit

Kurdish demands for greater autonomy by cracking down on protests and arresting

political leaders.

A Kurdish fighter from the Popular

Protection Units (YPG) shows his weapon decorated with its flag in Aleppo, Syria

(7 June 2014)

The Popular Protection Units (YPG) began

clashing with Islamist and jihadist rebel groups in Syria in 2013

The Kurdish enclaves were relatively

unscathed by the first two years of the Syrian conflict. The main Kurdish

parties avoided taking sides. In mid-2012, government forces withdrew to

concentrate on fighting the rebels elsewhere, after which Kurdish groups took

control.

The Democratic Unity Party (PYD) quickly

established itself as the dominant force, straining relations with smaller parties

who formed the Kurdistan National Council (KNC). They nevertheless united to

declare the formation of a Kurdish regional government in January 2014. They

also stressed that they were not seeking independence but "local

democratic administration".

IS meets its match in Kobane as Syria's Kurds fight to keep out jihadists.

Will Iraq's Kurds gain independence?

Mulla Mustafa Barzani, leader of the

Kurdistan Democratic Party, holds hands with Saddam Hussein, then deputy

chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council of the Iraqi Baath Party (20

March 1970) A peace deal agreed by the KDP and Iraq's

Baathist government in 1970 collapsed four years later.

|

| KDP's official logo |

Kurds make up an estimated 15% to 20% of

Iraq's population. They have historically enjoyed more national rights than

Kurds living in neighbouring states, but also faced brutal repression.

Kurds in the north of Iraq revolted against

British rule during the mandate era, but were crushed. In 1946, Mustafa Barzani

formed the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) to fight for autonomy in Iraq.

After the 1958 revolution, a new constitution recognised Kurdish nationality.

But Barzani's plan for self-rule was rejected by the Arab-led central

government and the KDP launched an armed struggle in 1961.

In 1970, the government offered a deal to

end the fighting that gave the Kurds a de facto autonomous region. But it

ultimately collapsed and fighting resumed in 1974. A year later, divisions

within the KDP saw Jalal Talabani leave and form the Patriotic Union of

Kurdistan (PUK).

Iraqi Kurdish refugees take shelter at a

refugee camp in south-eastern Turkey after fleeing fighting between Iraqi

government forces and Peshmerga in May 1991. Some 1.5 million Iraqi Kurds fled into Iran

and Turkey after the 1991 rebellion was crushed.

In the late 1970s, the government began

settling Arabs in areas with Kurdish majorities, particularly around the oil-rich

city of Kirkuk, and forcibly relocating Kurds. The policy was accelerated in

the 1980s during the Iran-Iraq War, in which the Kurds backed the Islamic

republic. In 1988, Saddam Hussein unleashed a campaign of vengeance on the

Kurds that included the poison-gas attack on Halabja.

When Iraq was defeated in the 1991 Gulf War

Barzani's son, Massoud, led a Kurdish rebellion. Its violent suppression

prompted the US and its allies to impose a no-fly zone in the north that

allowed Kurds to enjoy self-rule. The KDP and PUK agreed to share power, but

tensions rose and a four-year internal conflict erupted in 1994.

Massoud Barzani's KDP and Jalal Talabani's

PUK share power in the Kurdistan Region

The two parties co-operated with the US-led

invasion of Iraq in 2003 that toppled Saddam Hussein and have participated in

all governments formed since then. They have also governed in coalition in the

Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), created in 2005 to administer the three

provinces of Dohuk, Irbil and Sulaimaniya.

|

| Jalal Talabani and Massoud Barzani |

After the IS offensive in June, the KRG

sent the Peshmerga into disputed areas claimed by the Kurds and the central

government, and then asked the Kurdish parliament to plan a referendum on

independence.

However, it is unclear whether the Kurds

will press ahead with self-determination, or push for a more independent entity

within a federal Iraq.

Thank you so much, I hope this gave you an insight into who the us Kurds are and what Kurdistan is. Next post will include the different groups in Kurdistan.